Today, it is still true that States are the main constituent members of the international community. International law is the  entire set of rules that regulate relations among States. More specifically, international law consists of treaties and customary international law. Treaties include bilateral treaties, such as the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan, and multilateral treaties, in which many countries in international relations participate. Customary international law is usually considered to apply to all States in the international community.

entire set of rules that regulate relations among States. More specifically, international law consists of treaties and customary international law. Treaties include bilateral treaties, such as the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan, and multilateral treaties, in which many countries in international relations participate. Customary international law is usually considered to apply to all States in the international community.

However, the rules that regulate State behavior are, in reality, not limited to the traditionally established sources of international law mentioned above. In fact, the rules that are actually functioning in international relations are more diverse. For example, the Atlantic Charter (1941) and the Cairo Declaration (1943), which were adopted during the Second World War, are not treaties but played an extremely significant role in establishing the postwar world order. As a more recent example, the Joint Communique of the Government of Japan and the Government of the People’s Republic of China (1972) and the Helsinki Final Act (1975) are also not treaties, even though they were extremely important international agreements.

Recently, these documents are collectively called soft law. My research deals with what kind of role soft law plays in international relations. For example, there may be cases in which, with time, a soft law instrument transforms into a treaty or a rule of customary international law. In addition, by functioning alongside treaties, soft law may play a special role in this era of globalization.

1. Discovery of situations where soft law exists and functions, by reviewing previous studies and international cases and precedents

2. Formulation of specific conditions for successful functioning of soft law

3. Exploration of the diverse roles of agreements in international relations

Gentlemen’s agreements have existed since the prewar era (e.g., the Lansing–Ishii Agreement (1917)). This kind of agreement mainly functions among two or a small number of States.

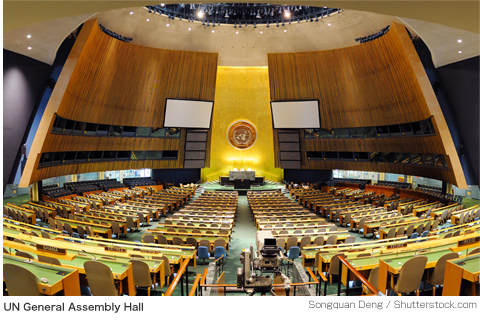

The United Nations, which was established after the Second World War, deserves to be specially mentioned in this respect. Although the General Assembly of the United Nations does not have authority to legislate rules of international law, it has adopted resolutions that declare principles of international law in a generalizable form (e.g., the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples (1960)) since its early days.

It was considered that these declarations would be a proof of lex lata, or lead to subsequent formation of customary international law. In particular, Third World countries tried to modify existing international laws through UN General Assembly resolutions and create new rules of international law. In other words, they tried to use the General Assembly as a sort of world parliament. This kind of movement seriously challenged traditionally established theory of the sources of international law.

Incidentally, codes of conduct of multinational enterprises and orderly marketing agreements (OMA) were created (as a result of trade rifts among developed countries) in the latter half of the 1960s and in the 1970s. These agreements concerned international economic relations and had quite significant impacts on the actual behavior of States and private corporations. This also blurred the distinction between hard law and soft law in international law.

With extremely cautious statements in its advisory opinion on Namibia in 1971, the International Court of Justice admitted the legal significance of the UN General Assembly concerning the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples. In the Nicaragua Case in 1986, the Court also mentioned that some General Assembly resolutions showed opinio juris sive necessitatis, which is one of the requirements for establishing a rule of customary international law.

Against this backdrop, it was recognized that international relations were regulated by not only treaties and customary international law, but also agreements, which although extremely important, were not legally binding. As a result, soft law theory emerged and became refined simultaneously.

Still, it is not easy to formulate the requirements and circumstances for soft law to effectively function in international relations. The reason is that soft law has many meanings, and there are a substantial variety of soft law instruments. For example, in the case of a bilateral non-binding agreement, it functions almost identically to regular treaties. A good example is the Japan–China Joint Communique.

On the other hand, in the case of UN General Assembly resolutions or some similar instruments which have normative significance, it is usually expected that they function as a part of customary international law process. Therefore, in such a case, if these documents are to play a significant role in international legal processes, resolutions need to be adopted with an intention to declare that it will be a part of customary international law process, or to be adopted unanimously or by overwhelming majority.

In addition, in terms of international economic relations, it is important how sufficiently a soft law instrument reflects the intentions of the parties concerned. Accordingly, it should be based on technical expertise and clear understanding of the intentions of the parties.

Active discussions on soft law resumed in the 1990s and have continued ever since. In contrast to the previous macro-level approach, these discussions have been conducted from a micro-level perspective, with focus on how States, NGOs, and individuals comply with soft law.

In relation to such discussions, detailed studies have been conducted covering various issues including highly specialized areas that would not have been previously heeded. Also, it used to be implicitly assumed that soft law would lead to formation of rules of customary international law in a linear fashion. Soft law would be also supposed to provide proof of customary international law rules. However, recent debates have focused on the role of soft law in the international legal process that are more complex and integrative. My presentation at the annual conference of the Japanese Society of International Law held in the fall of 2012 also mentioned this point.

Is the idea that consensus in international relations is formed exclusively by states still valid?

Before the end of the twentieth century, there was substantially no problem with saying that consensus in international relations could be created exclusively by States. However, as textbooks of international law in Europe and the United States point out, NGOs played a significant role in the adoption of the Statute of the International Criminal Court (1998). The idea that treaties are concluded exclusively by States became no longer appropriate. However, such a view is still unusual in Japan.

Looking at the actual international legal process, it is apparent that soft law plays a significant role, and that this fact has not been given sufficient attention. It is no longer appropriate to look at only treaties and customary international law. Considering this reality, the theory of consensus in international relations is ready to be reconstructed.

The Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (the SPS Agreement), which is a constituent part of the World Trade Organization Agreement, stipulates compliance with the standards adopted by the Codex Alimentarius Commission as the international standard. However, the Commission is not an international organization in the strict sense of the term. In other words, through the SPS Agreement, States agree beforehand to comply with the standards adopted by a non-governmental organization, instead of an agreement between States. This substantially undermined the role that traditionally established sources of international law should have played.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea stipulates that coastal states and flag States can create laws and regulations regarding prevention of marine pollution and requires that such laws and regulations should follow “generally accepted international rules and standards (GAIRS) established through the competent international organization or general diplomatic conference.” The International Maritime Organization (IMO) is considered to be such an international organization. This approach was formulated to respond to rapidly changing international relations, without amending the treaty itself. In any case, the norm-setting documents adopted by such organizations are not treaties or rules of customary international law. Although these documents are soft law instruments, they have great significance in the prevention of marine pollution by coastal States and flag States in reality.

The Operational Policies of the World Bank, which was internally adopted by the organization for its staff, have had a significant impact on the rights of indigenous people and the development of international environmental agreements.

A characteristic of today’s international law is that the process of its development is in fact significantly influenced by norm-setting documents adopted by highly specialized organizations. It is also observed that internal rules of international organizations, although not originally intended to be externally published, have a large impact on the development of the rules of international law.

Faculty of Liberal Arts

Professor

Biography

Education and professional experienceEducation

1995: Associate Professor, Miyagi University of Education

2001: Associate Professor, Faculty of Liberal Arts, Saitama University1981: Bachelor’s degree, College of Liberal Arts, International Christian University

1988: Master’s degree, Graduate Schools for Law and Politics, University of Tokyo

1993: Completed all course works except dissertation, Graduate Schools for Law and Politics, University of Tokyo

1995: Associate Professor, Miyagi University of Education

2001: Associate Professor, Faculty of Liberal Arts, Saitama University

Publications

Lectures in International Law (in Japanese, 2nd ed.). Tokyo: Yuhikaku Publishing, 2010. (with co-authors)

International Law (in Japanese, 2nd ed.). Tokyo: Yuhikaku Publishing, 2010. (with co-authors)

© Copyright Saitama University, All Rights Reserved.